Grading “Making The Grade?”: NCSE teacher ambassadors react

NCSE teacher ambassadors, from left to right: Kim Parfitt, Melinda Landry, and Rebecca Brewer.

In theory, the connection between state science standards and the science classroom is clear: the standards specify what knowledge and abilities students are expected to gain in the science classroom.

The reality can be a bit less straightforward.

Do teachers actually teach to the standards? What if the standards are subpar — inaccurate or inappropriate? What if the local community is hostile to the ideas contained in the standards? How might a teacher handle situations like these? And how else do standards affect the day-to-day work of science teachers?

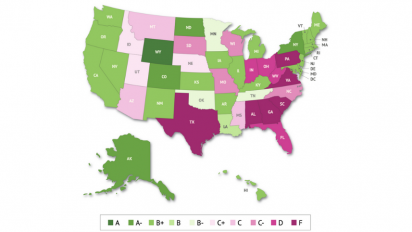

Recently, NCSE teamed up with the Texas Freedom Network Education Fund to assess the treatment of climate change in science standards from all 50 states and created a report card of sorts: “Making the Grade? How State Public School Standards Address Climate Change” (dive into our write-up of the report and read this perspective from the president of TFN). Since publication of the report, there have been newspaper editorials decrying the situation in states that received poor marks, and responses from departments of education acknowledging the shortcomings of their standards or protesting that they promote climate change education in different ways. But we were curious: do those in the trenches — the science teachers — care about a report like this, and what do they make of its findings?

So we touched base with three of our Teacher Ambassadors — master teachers from across the country — to get their take on the significance of the report and their reaction to the grade each of their state’s science standards received when it came to climate change.

“I shared this report with a number of people,” says Kim Parfitt, who taught earth science, biology, and AP biology for nearly 20 years in Wyoming, a state that received an A for its treatment of climate change.“ And they were gob-smacked.” Wyoming, Parfitt acknowledges, would probably not be at the forefront of most people’s minds as a place where climate change education has a strong foothold, given the importance of fossil fuel production to the state’s economy. But, she says, the Wyoming she knows takes climate change — and potential solutions, such as wind-generated power — seriously.

That said, Parfitt points out there can be a disconnect between the state standards and actual classroom instruction. “People could misinterpret and say Wyoming is getting an A in climate change classroom instruction. And I don’t know if that’s the case. I don’t know if anyone has evaluated what’s actually being taught.”

Melinda Landry, a high school environmental science and biology teacher in Virginia — a state that received an F — echoes that point. “These standards and that grade don’t represent what’s happening in the classroom—at least among the teachers I know,” she says. Landry points out that the state’s curriculum framework, based upon the state’s science standards and meant to articulate specific content knowledge and skills, is ultimately more of a polestar for teachers. “In my curriculum framework for AP environmental science, it’s clearly spelled out — all the key points that the report reviewers looked for,” Landry says.

“The human effect, what climate change is doing to biodiversity, what it’s doing to humans across the planet, possible solutions. So I make sure it’s clearly spelled out in my classroom, too.”

Though teachers may not necessarily teach to the standards, Landry believes that identifying climate change in state science standards does mean the topic is more likely to be covered. Rebecca Brewer, a high school biology teacher from Michigan (which received a B+), agrees.

“If it’s in the science standards, even if you’re unsure about climate change, you probably realize it’s your job, that you have to teach this.”

Parfitt says having strong climate change standards — which in the case of Wyoming have been created by local representatives from districts around the state—can provide support for teachers who are dealing with students, parents, and even administrators who may be climate change skeptics. “If teachers do run into conflict, they can say, ‘This is what I actually need to be teaching.’”

Ultimately, Brewer sees the “Making the Grade?” report as a call to action.

“I don’t think a B+ is acceptable,” Brewer says of Michigan’s grade.”I think we all need to aim higher. This is about our future, about having a sustainable environment for future generations. It’s too important for all of us not to want to be As. And if you’re already an A? Figure out how you can keep improving on instructional practices.”

Whether your state’s science standards got an F, an A, or a score in between, there’s room for improvement. And the stakes couldn’t be higher.

This article has been modified slightly from its original print format.